Early Celtic crosses, circa 600 AD were simply carved out of rock. By the 8th, 9th and 10th Centuries, high crosses became common to honour famous people or places. The Cross of the Scriptures, or King Flan's Cross, is inscribed with images of the Bible: the Last Supper, the Crucifixion and the Guarding of the Tomb. By the 1850's, it became common to use Celtic crosses as tombstones, a tradition continued in North America and Australia where Irish or Scottish immigrants have settled.

"History is a gallery of pictures in which there are few originals and many copies." (Alexis de Tocqueville)

Friday, 31 March 2017

The Celtic Cross

Just as St. Patrick made the shamrock into a Christian symbol he did the same with the Celtic cross. He took an ancient symbol of the sun and combined it with a Christian cross to form the Celtic cross. Across Ireland, Scotland and England, one can find Celtic crosses in many cemeteries. The Celtic cross had a practical component too; the circle strengthened the cross beams preventing breakage or destruction.

Early Celtic crosses, circa 600 AD were simply carved out of rock. By the 8th, 9th and 10th Centuries, high crosses became common to honour famous people or places. The Cross of the Scriptures, or King Flan's Cross, is inscribed with images of the Bible: the Last Supper, the Crucifixion and the Guarding of the Tomb. By the 1850's, it became common to use Celtic crosses as tombstones, a tradition continued in North America and Australia where Irish or Scottish immigrants have settled.

\

\

Early Celtic crosses, circa 600 AD were simply carved out of rock. By the 8th, 9th and 10th Centuries, high crosses became common to honour famous people or places. The Cross of the Scriptures, or King Flan's Cross, is inscribed with images of the Bible: the Last Supper, the Crucifixion and the Guarding of the Tomb. By the 1850's, it became common to use Celtic crosses as tombstones, a tradition continued in North America and Australia where Irish or Scottish immigrants have settled.

Thursday, 30 March 2017

William Butler Yeats Earns Nobel Prize

"'O words are lightly spoken'

Said Pearse to Connolly

'Maybe a breath of politic words

Has withered our rose tree

Or maybe but a wind that blows

Across the bitter sea.'"

(The Rose Tree, an imagined conversation between political radicals Pearse & Connolly after the Easter Rising of 1916)

Using the symbolist style, Yeats crafted dozens of poems including:

- Lake Isle of Innisfree (1890)

- The Wanderings of Oisin (1889)

- Song of the Old Mother (1899)

- Adam's Curse (1902)

- Easter (1916)

- The Rose Tree (1916)

- The Second Coming (1919)

- A Prayer for my Daughter (1921)

- Sailing to Byzantium (1928)

- Remorse for Intemperate Speech (1933)

Wednesday, 29 March 2017

The River Shannon

Legend has it that Rowan trees once dropped bright red berries into a well where they were eaten by silver fish, earning them great wisdom. Irish fishermen would catch the fish, hoping to share in this wisdom, but women were banned from the well. One day, a rebel woman named Sionan fished in the well and caught a silver fish. Suddenly, a great floodburst carried her west to the sea. The body of water became known as the Shannon, after the woman.

The River Shannon, Irelands longest river, provides a natural barrier between Northern Ireland and Ireland. The river spans 200 miles before it pours into the Atlantic Ocean. Along its banks sit historic towns, castles and monasteries. Key military battles have taken place along its shores. Its floodplain contains marshy grasslands and bogs ideal for birds.

While the silver fish, or Atlantic salmon, still swim in the Shannon, attracting anglers to the area. In the fall, the adult salmon swim upstream from the ocean into the river to spawn, capable of leaping a ten foot waterfall. The following spring, the baby salmon are born. As they grow older, they acquire vertical bars, silver in colour. Some Atlantic salmon spawn for multiple years unlike the Pacific salmon which die after spawning. Once tens of thousands of fish used to return each year, but now only a few thousand do.

The River Shannon, Irelands longest river, provides a natural barrier between Northern Ireland and Ireland. The river spans 200 miles before it pours into the Atlantic Ocean. Along its banks sit historic towns, castles and monasteries. Key military battles have taken place along its shores. Its floodplain contains marshy grasslands and bogs ideal for birds.

While the silver fish, or Atlantic salmon, still swim in the Shannon, attracting anglers to the area. In the fall, the adult salmon swim upstream from the ocean into the river to spawn, capable of leaping a ten foot waterfall. The following spring, the baby salmon are born. As they grow older, they acquire vertical bars, silver in colour. Some Atlantic salmon spawn for multiple years unlike the Pacific salmon which die after spawning. Once tens of thousands of fish used to return each year, but now only a few thousand do.

Tuesday, 28 March 2017

Molly Malone Statue

"In Dublin's fair city

Where the girls are so pretty

I first set my eyes on sweet Molly Malone

As she wheeled her wheel barrow

Through streets broad and narrow

Crying "Cockles and mussels, alive, alive, oh!"

For Dublin's millennium celebration, a statue of Molly Malone, a beautiful bosomy belle, was unveiled in 1988. The fictional character, featured in the song "Cockles and Mussels", was a fishmonger by day and a prostitute by night. Molly sold cockles and mussels out of her wheelbarrow. Sadly, one day Molly, suffering from a high fever, succumbed to a bout of cholera and passed away. Supposedly, her ghosts haunts the streets of Dublin now. The song was first published in Boston, Massachusetts in 1876.

Molly's statue, which sat at the bottom of Grafton Street, was temporarily removed to make way for a new track. Plans are underway to return it to its original location in 2017. It is known colloquially as "The Tart with the Cart" or "The Trollop with the Scallop(s)". Supposedly, a Mary (for which Molly is a nickname) Malone passed away on June 13, 1699, the date designated for Molly Malone Day.

Monday, 27 March 2017

Ireland's Shamrock Business: It All Started with a Workshop

"So a few of us got together and formed a company to license the technology that came from University College Dublin -- and the rest is history." (James O'Leary)

Twenty years ago, a group of Irish farmers attended a workshop on how to grow shamrocks in gel and the modern shamrock business was born. For decades, the shamrock, a three-leafed plant used by St. Patrick to demonstrate the Trinity, had grown in muddy glens. When they were pulled out of the soil, their roots were lost, thereby limiting their life. However, the workshop taught the farmers how to grow shamrocks in a hydroponic gel, thereby leaving the root intact and lengthening the life of the plant.

The shamrocks sell for about 10 Euros per plant or 45 Euros for a skillet full. Irish Plant International produces over 130,000 shamrock plants annually. While 4/5 of Ireland's shamrock plants stay on the Emerald Isle, the other 1/5 is shipped all over the world for St. Patrick's Day including places as far flung as Texas, Chile and Argentina. Shamrock lapels are worn for weddings and other special occasions. In a nod to his Irish roots, former president Barack Obama was given a vase of Shamrocks on St. Patrick's Day this year.

For more information about the St. Patrick and the shamrock, visit http://alinefromlinda.blogspot.ca/2017/03/st-patrick-kidnapped-by-pirates.html.

Sunday, 26 March 2017

When Erin First Rose

"When Erin first rose from the dark swelling flood,

God bless'd the green island and saw it was good;

The emerald of Europe, it sparkled and shone

In the ring of the world the most precious stone.

In her sun, in her soil, in her station thrice blest,

With her back towards Britain, her face to the West,

Erin stands proudly insular, on her steep shore,

And strikes her high harp 'mid the ocean's deep roar."

It was poet, physician and political radical, William Brennan who coined the term "Emerald Isle" in his poem dedicated to Ireland called When Erin First Rose written in 1795. Its verdure does not come from its deep forests for they were removed in the massive clearing efforts of the 1600's. The deep green shade comes from Ireland's lush green grass thanks to its wet climate. While Ireland is on the latitude of Newfoundland, which receives plenty of snow in the winter, Ireland benefits from the North Atlantic Drift which pushes the warm gulf stream towards the isle, keeping the temperature above freezing. Annual rainfall along the west coast can exceed 120 inches. The abundance of lush grass is a perfect place for livestock to graze. In fact, Ireland's eight million sheep and seven million cows outnumber its four and a half million people. (http://wonderopolis.org/wonder/where-is-the-emerald-isle)

Saturday, 25 March 2017

Maeve Binchy's Writing Career Started on a Kibbutz

Five year old Maeve Binchy with sister Joan and cousin Dan circa 1944 courtesy http://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/maeve-binchy-my-thoughts-on-ireland-crpdx5tpdcz.

Maeve Binchy, the Irish author of 16 novels about small town life in Ireland, started her career as a teacher of French and Latin. One summer, the parents of a student gave her a free trip to Israel. She spent her days picking oranges and tugging chickens on a kibbutz, and her evening writing letters home to her parents. Her father thought the letters were so eloquently written that he cut off the salutation and sent them to the newspaper where they were published. These letters sparked Binchy's career as a journalist.

Michele Bachmann worked on a kibbutz in Israel in the 1960's just like Maeve Binchy courtesy http://cdn.timesofisrael.com/uploads/2012/08/downloadedfile_0.jpeg/

Binchy went on to write a total of 24 books, 16 of which are novels. Most of her novels dealt with the contrast between rural and urban life, between England and Ireland and between World War II Ireland versus today's Ireland. Ironically, the author ended up marrying an Englishman, Gordon Snell, who was a BBC producer in London. They lived in England for a time and later moved to Binchy's beloved Ireland where Snell became a children's author.

Gordon Snell & Maeve Binchy walk along the sea jetty courtesy http://www.gettyimages.ca/photos/gordon-snell.

Friday, 24 March 2017

The Irish Cottage

In 1840, 40% of Irish families lived in one room thatched cottages. Here are ten things you may not know about the Irish cottage.

1. A fireplace or hearth, built of stone, was located in the middle of the house, often with a bedroom on either end.

2. Roofs were usually constructed of coupled rafters stuffed with turf for insulation and thatched to prevent leaking water.

3. A primary source of timber was wood washed ashore from wrecked ships.

4. For those with more money, there was the thatched mansion, a two story cottage. The Old Farm Cottage in Kilkenny is one example.

5. The half door had three purposes: it kept the children in and the animals out; it permitted light and air to circulate in the damp and dusty cottage; it served as a prop to lean on while smoking a pipe.

6. The Irish cottage was filled with a couple, their six or seven children, a pig and a dresser of hens or chickens.

7. Irish cottages often had two doors, one entrance for the mother in law, the other for the daughter in law.

8. Irish cottages usually had small windows, limited in number. The size was to keep the heat in, the number to prevent being taxed for having more than six windows, a law enforced between 1799 and 1851.

9. Water was supplied by a well, located by a local diviner with a divining rod.

10. The "good room" sometimes added on to cottages at a later date, was the parlour, reserved for guests like priests or teachers.

1. A fireplace or hearth, built of stone, was located in the middle of the house, often with a bedroom on either end.

2. Roofs were usually constructed of coupled rafters stuffed with turf for insulation and thatched to prevent leaking water.

3. A primary source of timber was wood washed ashore from wrecked ships.

4. For those with more money, there was the thatched mansion, a two story cottage. The Old Farm Cottage in Kilkenny is one example.

5. The half door had three purposes: it kept the children in and the animals out; it permitted light and air to circulate in the damp and dusty cottage; it served as a prop to lean on while smoking a pipe.

6. The Irish cottage was filled with a couple, their six or seven children, a pig and a dresser of hens or chickens.

7. Irish cottages often had two doors, one entrance for the mother in law, the other for the daughter in law.

8. Irish cottages usually had small windows, limited in number. The size was to keep the heat in, the number to prevent being taxed for having more than six windows, a law enforced between 1799 and 1851.

9. Water was supplied by a well, located by a local diviner with a divining rod.

10. The "good room" sometimes added on to cottages at a later date, was the parlour, reserved for guests like priests or teachers.

Thursday, 23 March 2017

No Irish Need Apply

The Potato Famine of the 1840's drove thousands of Irish farmers out of the country. Many immigrated to England, Australia and North America with the hope of starting over. However, when they looked for work in their new country, they were often greeted by a window sign saying: "Irish Need Not Apply".

The phrase turned up 29 times in the New York Times on November 10, 1854. A variation, Irish Need Not Apply" appeared 7 times. Other ads specified interest in Americans or Protestants, appearing several times on May 1, 1855, which effectively eliminated Irish Catholics.

A song "No Irish Need Apply", written by Kathleen O'Neil, was inspired by a young Irish woman searching for work as a maid in London. She spots a sign in a window which reads: "A small active girl to do the general housework of a large family, one who can cook, clean and get up fine linen, preferred. No Irish Need Apply."

(The London Times, February, 1862)

Nineteenth Century British writer Anthony Trollope explained the pervading sentiment at the time:

"Often depicted as monstrous beings or apes in satirical cartoons, the Irish were not seen as welcome members to English society. Irish immigrants were seen as lazy, drunk, anarchistic criminals whose sole purpose in life was to steal the jobs of English workers. It comes as no surprise, then, that English employers were not very welcoming of Irish workers."(https://apps.cndls.georgetown.edu/projects/borders/items/show/86)

The city of Boston, Massachusetts was a common destination for the Irish. In one year, the Eastern Seaboard city swelled from 30,000 to 100,000 Irish. Boston shop windows often displayed the trademark "No Irish Need apply" signs, relegating the Irish to the most menial jobs. In fact, in the mid-1800's, 70% of Boston's servants were Irish. But they got their foot in the door.

The influence of Irish Catholics slowly grew when the Irish accepted jobs in the police force and in politics. John Francis "Honey Fitz" Fitzgerald, father of the future Rose Kennedy, became mayor of Boston in 1906. Joseph P. Kennedy rose to be the American Ambassador to Britain during the Second world War. His son, John F. Kennedy, of course, became the 35th President of the United States in 1961, the first Catholic to be elected to the position.

Today, No Irish Need Apply signs are proudly mounted in the suburban Boston homes of third, fourth and fifth generation Irish. (http://www.bostonmagazine.com/2006/05/no-irish-need-apply/)

The phrase turned up 29 times in the New York Times on November 10, 1854. A variation, Irish Need Not Apply" appeared 7 times. Other ads specified interest in Americans or Protestants, appearing several times on May 1, 1855, which effectively eliminated Irish Catholics.

A song "No Irish Need Apply", written by Kathleen O'Neil, was inspired by a young Irish woman searching for work as a maid in London. She spots a sign in a window which reads: "A small active girl to do the general housework of a large family, one who can cook, clean and get up fine linen, preferred. No Irish Need Apply."

(The London Times, February, 1862)

Nineteenth Century British writer Anthony Trollope explained the pervading sentiment at the time:

"Often depicted as monstrous beings or apes in satirical cartoons, the Irish were not seen as welcome members to English society. Irish immigrants were seen as lazy, drunk, anarchistic criminals whose sole purpose in life was to steal the jobs of English workers. It comes as no surprise, then, that English employers were not very welcoming of Irish workers."(https://apps.cndls.georgetown.edu/projects/borders/items/show/86)

The city of Boston, Massachusetts was a common destination for the Irish. In one year, the Eastern Seaboard city swelled from 30,000 to 100,000 Irish. Boston shop windows often displayed the trademark "No Irish Need apply" signs, relegating the Irish to the most menial jobs. In fact, in the mid-1800's, 70% of Boston's servants were Irish. But they got their foot in the door.

The influence of Irish Catholics slowly grew when the Irish accepted jobs in the police force and in politics. John Francis "Honey Fitz" Fitzgerald, father of the future Rose Kennedy, became mayor of Boston in 1906. Joseph P. Kennedy rose to be the American Ambassador to Britain during the Second world War. His son, John F. Kennedy, of course, became the 35th President of the United States in 1961, the first Catholic to be elected to the position.

Today, No Irish Need Apply signs are proudly mounted in the suburban Boston homes of third, fourth and fifth generation Irish. (http://www.bostonmagazine.com/2006/05/no-irish-need-apply/)

NINA sign circa 1916 courtesy Fulton Street Sign Co.

Wednesday, 22 March 2017

To Hell or to Connaught!

"If this people shall headily run on after their Prelates and other Clergy and other leaders, I hope to be free from the misery and desolation, blood and ruin that shall befall them, and shall rejoice to exercise utmost authority against them." (Oliver Cromwell)

Irish Catholics were driven out of their homeland in 1649 to Connaught courtesy https://www.pinterest.com/pin/367606388305894164/.

In 1649, Oliver Cromwell decreed that all Irish Catholics were to be banished to one of the four provinces of Ireland, the poorest one, while the three remaining provinces were reserved for English settlement. "To hell or to Connaught!" became the battle cry.

After King Charles I was beheaded in January of 1649, Oliver Cromwell was sent to Ireland to bring the Royalist Army into submission. Cromwell took the opportunity to purge much of the area of the Irish inhabitants. The Irish Catholics started to flee over the Shannon River but not all of them made it in time. A group of men women and children, seeking refuge in a church in Drogheda, were slaughtered. Cromwell explained: "I put all of them to the sword but 30, and they are on their way to Barbados. I believe that all their Friars were knocked on the head but two, the one of which was Fr. Peter Taaff whom the soldiers took the next day and made an end to him..."

The Act for the Settlement of Ireland of 1652 was a reaction to the Irish Rebellion of 1641. Participants and bystanders would either be killed or have their land confiscated. Some say that Connaught was chosen because it was the poorest province of Ireland. Others say that this was the English Protestants' way of keeping the Irish Catholic landowners "penned between the sea and the River Shannon."

While Irish Catholics were threatened with death, it is a myth that they were all killed. Rather their land was confiscated and they became servants to the new English landowners. The servants and their descendants worked the land and paid taxes to the English for the land that they used to own for almost 200 years. The Potato Famine hit, decimating the population. Ireland's population would never recover.

Note: Today, St. Patrick's Day is only an official holiday in Ireland and Montserrat, the destination of the fleeing Irish Catholics in 1649.

Siege of Drogheda site courtesy

Tuesday, 21 March 2017

Killarney National Park

Ross Castle courtesy http://www.chooseireland.com/kerry/ross-castle/.

At the foot of the McGillicuddy Reeks, Ireland's highest mountains, are nestled the Killarney Lakes. Here lies a 26,000 acre filled with woods and waterfalls, red deer and red squirrels, called Killarney National Park.

One of the highlights of the park is Ross Castle, built by O'Donohue Mor in the 15th Century. Later O'Donohue leased the land to the Brownes, later the Earls of Kenmare. Ross Castle was one of the last to be taken by Oliver Cromwell's Roundheads during the Irish Confederate Wars. The Roundheads marched to the castle with 4000 soldiers and 200 horses, but it wasn't until artillery arrived via the River Laune that the castle was finally taken. In 1688, the Brownes erected a mansion near the castle but were exiled due to their allegiance to James II of England. The castle became a military barracks while the Brownes built Kenmare House to reside in. A group of American businessmen bought the castle and a large part of the Kenmare estate in the 1950's, intent on developping the area. However, they sold the castle to the Irish state for a nominal fee and, in the 1970's, renovations began. The castle reopened to the public in 1991.

Torc Waterfall, about five miles from Killarney, is another popular destination for tourists. Fed by the Owengarriff River, it rises 70 to 80 feet high. Tourists can climb a set of 100 steps to get a view of the lakes below.

Red deer in Killarney National Park courtesy https://www.hiddenirelandtours.com/day-excursions/day-walks-and-hikes/killarney-gap-of-dunloe-black-valley/.

The Oak and Yew Woodlands encompass 30,000 kilometres, much of which falls in Killarney National Park. Oak and beech trees are prevalent in the woods, home to Ireland's only native red deer. Birds native to the area are European robins and wrens while mammals include badgers and foxes. The highlight for many is the red deer.

Three lakes provide a breathtaking view for tourists including Muckross Lake, Upper Lake and Lough Leane. River Laune, the waterway used by Cromwell's Roundheads in the 15th Century, flows out of Lough Leane. Muckross Lake boasts many large natural caves carved out of the limestone. Brown trout and salmon populate the lakes, a popular site for sport angling.

The Purple mountains viewed from the Upper Lake courtesy https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Killarney_National_Park.

Monday, 20 March 2017

Irishman Who Designed Oscar Statuette Had Eleven on His Mantel

Oscar statuette is a knight standing on a film reel and holding a sword courtesy http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/01/23/oscar-films-sundance_n_6518866.html.

Born in 1893, Cedric Gibbons was an Irishman who made a name for himself in Hollywood. He not only designed the Oscar statuette, but was nominated for thirty eight and brought home eleven.

Edith Head holds the record for most Oscars won by a woman (8) courtesy https://www.blue17.co.uk/edith-head-incredible-designers/.

Austin Cedric Gibbons, the son of an architect, was born in Dublin in 1893. He studied at the Arts Students League of New York and was hired by MGM in 1924 as an art director and production designer. Four years later, he helped found the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. In 1928, it was Gibbons who designed the most recognized award in the world, the statuette of a knight standing on a reel of film gripping a crusader's sword. Oscar stands 13 1/2 inches tall and weighs 8 1/2 pounds, thanks to its solid bronze casting. Legend has it that the statuette got its name when the Academy librarian, Margaret Herrick, commented that it looked like her Uncle Oscar. In 1929, the first Academy Awards were held at the Roosevelt Hotel in Los Angeles where Janet Gaynor won a statuette for best actress and Emil Jannings for best actor.

First Academy Awards ceremony in 1929 courtesy https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1st_Academy_Awards.

Little did Gibbons know that one year after he designed the Oscar, he would be carrying the statuette home. In fact, when his career was done, Gibbons' mantel would hold a record-breaking 11 Oscars, and he would be nominated for 38. Gibbons influenced the production of about 1500 films and had direct involvement in 150 films in Hollywood. The art director won the Academy Award for the following movies:

- The Bridge of St. Louis Rey (1929)

- The Merry Widow (1934)

- Pride and Prejudice (1940)

- Blossoms in the Dust (1941)

- Gaslight (1944)

- The Yearling (1946)

- Little Women (1949)

- An American in Paris (1951)

- The Bad and the Beautiful (1952)

- Julius Caesar (1953)

- Somebody Up There Likes Me (1957)

Cedric Gibbons with his Oscars courtesy https://www.pinterest.com/slynnrich/cedric-gibbons/.

Sunday, 19 March 2017

Jigs, Reels & Hornpipes

Here are ten facts you may not know about Irish dancing:

1. Irish dancing was influenced by dancing on the Continent, especially the Quadrille, a type of square dancing performed by four couples in a rectangle.

2. Dance competitions in the 18th and early 19th Century were often held in close quarters and therefore were performed on table tops or barrel tops. The close quarters dictated the nature of the dance; for example, dancers kept their hands rigid at their sides and didn't travel much.

3. A ceili is a social gathering featuring Irish dance and music. Ceili dances can be performed by as few as two and as many as 16 and include "The Walls of Limerick" and "Haymaker's Jig".

4. Irish set dancing, based on the quadrille, follows the tempo of a jig, reel or hornpipe.

5. Irish step dancing includes sean-nos dancing and old style step-dancing. The most popular style is the Munster.

6. Irish dancers wear either soft shoes or ghillies (black lace up shoes) or hard shoes (similar to tap shoes).

7. Several generations ago, Irish dancers wore their Sunday best to compete. In the 1970's, they started wearing ornate costumes which they still wear today.

8. Irish dancers wear a wig, bun or hairpiece.

9. There are multiple traditional set dances including St. Patrick's Day, Blackbird, Job of Journey Work, Three Sea Captains, Garden of Daisies and King of Fairies.

10. Riverdance, which helped popularize Irish Dancing, first started as an interval act at the 1994 Eurovision Song Contest.

1. Irish dancing was influenced by dancing on the Continent, especially the Quadrille, a type of square dancing performed by four couples in a rectangle.

2. Dance competitions in the 18th and early 19th Century were often held in close quarters and therefore were performed on table tops or barrel tops. The close quarters dictated the nature of the dance; for example, dancers kept their hands rigid at their sides and didn't travel much.

3. A ceili is a social gathering featuring Irish dance and music. Ceili dances can be performed by as few as two and as many as 16 and include "The Walls of Limerick" and "Haymaker's Jig".

4. Irish set dancing, based on the quadrille, follows the tempo of a jig, reel or hornpipe.

5. Irish step dancing includes sean-nos dancing and old style step-dancing. The most popular style is the Munster.

6. Irish dancers wear either soft shoes or ghillies (black lace up shoes) or hard shoes (similar to tap shoes).

7. Several generations ago, Irish dancers wore their Sunday best to compete. In the 1970's, they started wearing ornate costumes which they still wear today.

8. Irish dancers wear a wig, bun or hairpiece.

9. There are multiple traditional set dances including St. Patrick's Day, Blackbird, Job of Journey Work, Three Sea Captains, Garden of Daisies and King of Fairies.

10. Riverdance, which helped popularize Irish Dancing, first started as an interval act at the 1994 Eurovision Song Contest.

Saturday, 18 March 2017

A Big, Bloody Problem

"The story of how Dubliners came to be printed is a fascinating tale of artistic frustration and persistence despite years of dismissal." (Sean Hutchinson)

James Joyce courtesy

http://mentalfloss.com/article/57437/long-and-difficult-publication-history-james-joyces-dubliners/.

In university I wrote an essay about James Joyce's short story collection Dubliners. I assumed that the publication was snapped up by a publisher when Joyce first wrote it early in the 20th Century. How wrong I was!

Back in 1904, Joyce, a starving "artist", was teaching English at the Berlitz School in Trieste, now part of Italy. He wrote a collection of three stories ("The Sisters", "Eveline", and "After the Race") which were printed in a weekly publication called The Irish Homestead. In the meantime, Joyce composed nine more stories, with the intent of publishing an anthology, which he sent to publisher Grant Richards.

Richards promptly drew up a contract which he mailed to Joyce and sent the manuscript to the printer. In the meantime, the printer, who at the time was just as libel as the publisher for the content of the publication, pointed out that Joyce's collection of stories contained obscenities. The story "Counterparts" talked about male and female anatomy while "Grace" contained the line: "Then he has a bloody big bowl of cabbage before him on the table and a bloody big spoon like a shovel.'

Joyce protested that the word bloody was used numerous times in his collection, but Richards remained firm. In 1906, the writer resubmitted the stories, this time with the offensive anatomy vocabulary removed as well as the word "bloody". Joyce included the note: "I think that I have injured these stories by these deletions but I sincerely trust that you will recognize that I have tried to meet your wishes and scruples fairly."

After months of waiting, Joyce was still rejected by Richards. He temporarily retained a lawyer to sue Richards for breach of contract but was talked out of the suit. In the meantime, he turned his efforts to his other collection Chamber Music which was published in 1907 thinking the milestone might gain him more clout with publishers, but such was not the case. Dubliners was promptly rejected by four other publishers in late 1907 and early 1908.

In the meantime Dublin publisher Maunsel & Co. expressed interest to read the manuscript for Dubliners but by this point Joyce was so gun shy it too him a year to work up the courage to submit it. In 1909. Maunsel drew up a contract for Joyce. But that obscenity word reared its ugly head again. Upon further inspection, the Maunsel publisher, Roberts, was disturbed by slanderous remarks in about the recently deceased King Edward VII in "Ivy Day in the Committee Room". Roberts postponed the publication of Dubliners once again.

Joyce refocussed his efforts by investing in a new cinema to be opened in Dublin until financial difficulties forced him to withdraw in July of 1910. Returning to his short story collection, he made some requested changes to it, but refused to take out the reference to King Edward VII. Roberts, equally stubborn, refused to publish the work. The daring Joyce wrote a letter to King George V asking him if he objected to the "Ivy Day" reference to his dead father. Joyce was surprised when he received a reply, albeit from the king's secretary, which stated: "It is inconsistent with rule for His Majesty to express his opinion in such cases." It seemed like the opinion was unanimous: everyone had left Joyce "hanging out to dry".

A downtrodden Joyce, not to be defeated, wrote a publication history of his precious Dubliners which was published by a few Irish newspapers, which included the King Edward VII reference. It was like a tree falling in the forest: no one heard. Joyce was forced to confront his publisher Roberts face to face, a meeting in which publisher compared the writer to The Giant's Causeway, massive stone cliffs in Northern Ireland. Roberts explained that the collection was decidedly anti-Irish and told Joyce to replace place names in "Counterparts" with fictitious ones, upon other demands.

The altered version finally made it to the printer where it was mysteriously destroyed, but not before Joyce obtained a copy "by ruse". Joyce later discovered that one of Maunsel & Co's biggest clients, Lady Aberdeen, was the head of the Irish Vigilance Committee, and could very likely have acted as a thorn in his side. In exile once again, he composed a poem about the whole fiasco called "Gas from a Burner (http://andromeda.rutgers.edu/~ehrlich/699/GASBURN") . The dejected writer hightailed it out of Dublin, never to return.

Joyce turned his attention towards Ulysses and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Finally in December of 1913, he received a letter from the original publisher, Richards, who expressed interest in the short story collection. Eight years after the original contract was signed for Dubliners, Richards offered him a second one. The stipulation, however, stated that Joyce would not receive royalties on the first 500 copies sold. Secondly, Joyce would have to purchase at least 120 copies himself. Publication went ahead in 1914, a full nine years after Joyce first penned the stories.

Dubliners sold 499 copies. Joyce received no royalties. But the cloud had a silver lining. In 1916, Dubliners was picked up by an American publisher, pushing his notoriety. It was Joyce's 1922 masterpiece, Ulysses, however, that gave him worldwide acclaim. Dubliners would prove to be an enduring work, however; a Canadian university student would write a paper about it in 1990.

James Joyce chatting with Shakespeare & Co Bookstore owner in Paris circa 1922 courtesy http://media.gettyimages.com/photos/author-james-joyce-chatting-with-shakespeare-co-bookstore-owner-picture-id72403313.

Friday, 17 March 2017

St. Patrick: Kidnapped by Pirates, Converted a Nation

He was born Maewyn Succat to Roman parents living in Scotland. At 16, Maewyn was kidnapped by Irish pirates and taken to Ireland where he worked as a slave for six years. Maewyn's time in captivity, during which he worked as a shepherd, was critical to his spiritual development. He prayed to God constantly to help him through his suffering. One day, he had a dream in which God said: "Your ship is ready." He escaped his captors and boarded a ship for France. In France, Maewyn trained as a Catholic priest.

Back in Scotland, he had another dream in which an Irishman visited him with several letters. One letter had the heading: "The Voice of the Irish". He imagined a collective voice saying to him: "We appeal to you, holy servant boy, to come and walk among us."

He later returned to Ireland, now St. Patrick, landing at Wicklow. Not receiving a warm welcome from the locals, he landed further north and set about working as a missionary. As a foreigner in Ireland he was occasionally beaten robbed or put in chains. Yet he persevered, sharing the Gospel with the locals. In his 30 years in Ireland, St. Patrick converted 135,000 Irish men and women to Christianity. He established 700 churches and consecrated 350 bishops and ordained 5000 priests. He refused to accept gifts from wealthy women whom he had converted, took no payments for baptisms or ordinations and turned down gifts from kings.

St. Patrick turned some of the pagan symbols in Ireland into Christian ones, including the shamrock. The three-leafed plant represents the Trinity, God the Father, God the Son and God the Holy Spirit. St. Patrick's Day, March 17, is believed to be the date of his death, celebrated for over a millennium.

Thursday, 16 March 2017

Nelson's Pillar

"Man and boy I have lived in Dublin, on and off, for 68 years. When I was a young fellow, we didn't talk about Nelson's Column or Nelson's Pillar, we spoke of the Pillar, and everyone knew what we meant." (Thomas Bodkin, radio broadcaster, 1955)

Vice Admiral Lord Nelson was a hero. Leading the Royal Navy, he had defeated both Spain and France in the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. Mortally wounded, he would die that day but not before victory was secured for both the Harp (Ireland) and the Crown (England). About a third of the Royal Fleet was Irish and 400 were from the City of Dublin. When news of Nelson's victory reached the city in November, Irish men and women celebrated in the streets.

The city aldermen declared that a memorial should be erected to the fallen hero and Lord Mayor established a "Nelson Committee". The committee invited artists and sculptures to submit design proposals. The typical architecture at the time was classical like the Trajan's Column in Rome. William Wilkins, an English architect, proposed a Doric column on a plinth surmounted by a sculpted Roman galley. Some people suggested that the memorial be erected at Dublin Bay or along the river. However, a site on Sackville Street was ultimately chosen.

By mid-1807 the "Nelson Committee" still fell far short of the required 6,500 pounds to erect the statue. Nevertheless, they went ahead with the laying of the foundation stone in early 1808. A memorial plaque, eulogizing Lord Nelson's victory, was laid with the foundation stone. By the time the project was complete in the fall of 1809, the committee had a surplus of 282 pounds. When complete, Nelson's Column stood 134 feet high. It opened on October 21, 1809, the fourth anniversary of Nelson's victory. Visitors could walk up 168 steps to the top of the column where they enjoyed a view of the city, the country and the bay.

Rubble from the General Post Office bombed during the Easter Rising 1916 courtesy http://www.post-gazette.com/life/lifestyle/2016/03/11/St-Patrick-s-Day-Parade-gives-a-nod-to-the-Easter-Rising-of-1916/stories/201603040208.

"For the next 157 years, its ascent was a must on every visitor's list." When Queen Victoria paid a visit to the city in 1849, citizens dubbed the column "Dublin's Glory". Yet only four years later, when the queen visited Dublin for the Industrial Exhibition, city planners considered removing Nelson's Pillar. Any action to remove or resite the Pillar would require an Act of Parliament in London, however. A city alderman suggested replacing the now "unsightly structure" with a memorial to Sir John Gray, who had contributed greatly to Dublin's clean water supply system. But the "pillar had become part of the fabric of the city".

The Easter Rising of 1916, sparked by a peaceful protest which turned deadly, caused massive destruction on Sackville Street. Several buildings burned to the ground including the General Post Office. However, Nelson continued to stand on his perch, almost oblivious to the melee. Other than a few bullet holes, the column remained standing. In fact, "the statue was visible, against the fiery backdrop, from as far away as Killiney, 9 miles away."

Nelson's Pillar remained in place on Sackville Street until March 8, 1966 when a bomb blasted the top half off leaving only a 70 foot stump. "There was an air of inevitability about the about Horatio Nelson's eventual demise: King William of Orange, King George II and Viscount Gough in the Phoenix Park had all fallen victim to republican bombings." (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nelson%27s_Pillar)

The rest of the Pillar was destroyed by the army on March 14. Some portions of it, including Nelson's head, are on display in museums. Lettering from the monument is now part of the Butler House walled garden.

Wednesday, 15 March 2017

Irish Wives Tales

1. Never ask a man going fishing where he's going.

2. If your shirt gets wet while you're washing dishes, you will marry a drunk.

3. If you find a horseshoe and nail it to the door, it will bring you good luck. THe same is not true however if the shoe is bought or given as a gift.

4. If you meet a magpie, a cat or a woman with a limp when you're on a trip, you will have bad luck.

5. If you kill a robin redbreast, you will never have good luck.

6. If a rooster comes to the thresh hold of your house and crows, expect visitors.

7. If you meet a funeral party on the road, you must turn and walk with the party for at least four steps to ward off bad luck.

8. If you trip and fall in a grave yard, you will most likely die by the end of the year.

9. If the first lamb of the year is black, someone in the family will die within the year.

10. It is unsafe to pick up an unbaptized child unless you make the sign of the cross.

Source: http://www.irishcentral.com/roots/four-leaf-clover-and-other-irish-superstitions-on-st-patricks-day-118164419-237791901

2. If your shirt gets wet while you're washing dishes, you will marry a drunk.

3. If you find a horseshoe and nail it to the door, it will bring you good luck. THe same is not true however if the shoe is bought or given as a gift.

4. If you meet a magpie, a cat or a woman with a limp when you're on a trip, you will have bad luck.

5. If you kill a robin redbreast, you will never have good luck.

6. If a rooster comes to the thresh hold of your house and crows, expect visitors.

7. If you meet a funeral party on the road, you must turn and walk with the party for at least four steps to ward off bad luck.

8. If you trip and fall in a grave yard, you will most likely die by the end of the year.

9. If the first lamb of the year is black, someone in the family will die within the year.

10. It is unsafe to pick up an unbaptized child unless you make the sign of the cross.

Source: http://www.irishcentral.com/roots/four-leaf-clover-and-other-irish-superstitions-on-st-patricks-day-118164419-237791901

Tuesday, 14 March 2017

Sunday, Bloody Sunday

U2 performing in Dublin circa 1981 courtesy

Last Sunday, our praise team performed an old U2 song. It brought back memories of my wedding reception and the song "Mysterious Ways". U2 is the most famous musical group to come out of Ireland. The band, originally an overtly Christian one, formed in 1976. Four years alter, they released their debut album, Boy. In 1983, they debuted the album War, which rose to number 1 on the UK charts.

The single "Sunday Bloody Sunday", featured on the War album, cemented the foursome as a socially conscious rock group. The tune focusses on an incident in Derry where troops open fired on hundreds of unarmed protesters rallying against Operation Demetrius related internment. After the smoke cleared, 13 people lay dead in the street. The incident would be known as part of The Troubles, a thirty year long period of political unrest in Northern Ireland from 1968 to 1998.

The band started performing Sunday Bloody Sunday, not as a terrorist song, not as a rebel song, but as a peace song, driven home by the white flag that Bono used to wave. The song's militaristic beat reminds us of the British troops while the violin reminds us of its Celtic roots. Sunday Bloody Sunday became a battle cry for peace around the world. U2 played it at their Live Aid performance. They also performed it nightly on their tour of war torn Yugoslavia in 1997.

Protest which turned violent on Bloody Sunday, 1972 courtesy http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/bloody_sunday.

Monday, 13 March 2017

Rocky Road to Dublin

"Rocky Road to Dublin" is a song written about the Irish capital (http://www.dublinlive.ie/whats-on/arts-culture-news/rocky-road-dublin-17-greatest-10948795). Here are some other interesting facts about Dublin, Ireland.

1. Dublin's O'Connell Bridge was originally made of rope and could carry only one man and one donkey. In 1801, it was replaced with a wooden structure and in 1863, a concrete one, first called "Carlisle Bridge".

2. Dublin's oldest workhouse, which closed in 1969, held 10,037 orphan children during its 170 years of operation.

3. Dublin, originally called Dubh Linn or Black Pool, was named after the oldest treacle (British term for molasses) lake in North Europe, and currently forms the centrepiece of the penguin enclosure of the Dublin Zoo.

4. The average Dubliner earns 19000 pounds per year and gives 12 pounds to charity and 162 pounds in tips.

5. The Dublin Mountains are technically not high enough to merit the name, the highest, Sugarloaf, reaches only 1389 feet above sea level.

6. Dublin's oldest traffic light is situated beside the Renault garage; the light, still in working order, was installed in 1893 outside the home of Fergus Mitchell, the first Dubliner to own a car.

7. In 1761, a family of itinerants from Navan, Ireland, was refused entry to Dublin. They settled in Rush on the outskirts of the city. Today, almost all 250 inhabitants there can trace their roots to this family.

8. Dubliners drink an average of 9800 pints an hour between Friday at 5:30 pm and Monday at 3:00 am.

9. Harold's Cross got its name from a tribe that lived in the Wickow Mountains. The Archbishop of Dublin wouldn't let them come any closer than that point.

10. Leinster Garden once had a large statue of Queen Victoria. However, it was removed when the Republic of Ireland was formed in 1948. In 1988, it was donated to Sydney Australia to mark their 200th Anniversary.

11. The largest cake every baked in Dublin, weighing 190 pounds, was made to celebrate the city's millennium in 1988. The cake, never eaten, was finally thrown out in 1991.

12. Dublin contains 46 rivers and streams including; Delvin, Hurley, Corduff, Finglas, and Shanganagh.

13. Nelson's Pillar was blown up in 1966 to mark the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising (http://alinefromlinda.blogspot.ca/2017/03/easter-rising-1916.html) . It now lies in a heap in the valley in County Wicklow.

14. Dublin contains five areas which end in the letter "O": Rialto, Marino, Portobello, Phibsboro, Pimlico.

15. The original name of Trinity College was Trinity College near Dublin. The city was a lot smaller when the college was founded.

Source: http://www.irelandrevealed.com/facts-and-interesting-stuff-about-dublin/45-facts-of-so-you-think-you-know-dublin/

1. Dublin's O'Connell Bridge was originally made of rope and could carry only one man and one donkey. In 1801, it was replaced with a wooden structure and in 1863, a concrete one, first called "Carlisle Bridge".

2. Dublin's oldest workhouse, which closed in 1969, held 10,037 orphan children during its 170 years of operation.

3. Dublin, originally called Dubh Linn or Black Pool, was named after the oldest treacle (British term for molasses) lake in North Europe, and currently forms the centrepiece of the penguin enclosure of the Dublin Zoo.

4. The average Dubliner earns 19000 pounds per year and gives 12 pounds to charity and 162 pounds in tips.

5. The Dublin Mountains are technically not high enough to merit the name, the highest, Sugarloaf, reaches only 1389 feet above sea level.

6. Dublin's oldest traffic light is situated beside the Renault garage; the light, still in working order, was installed in 1893 outside the home of Fergus Mitchell, the first Dubliner to own a car.

7. In 1761, a family of itinerants from Navan, Ireland, was refused entry to Dublin. They settled in Rush on the outskirts of the city. Today, almost all 250 inhabitants there can trace their roots to this family.

8. Dubliners drink an average of 9800 pints an hour between Friday at 5:30 pm and Monday at 3:00 am.

Sean's Bar, established in 900 AD, is Ireland's oldest pub courtesy https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sean's_Bar.

9. Harold's Cross got its name from a tribe that lived in the Wickow Mountains. The Archbishop of Dublin wouldn't let them come any closer than that point.

10. Leinster Garden once had a large statue of Queen Victoria. However, it was removed when the Republic of Ireland was formed in 1948. In 1988, it was donated to Sydney Australia to mark their 200th Anniversary.

11. The largest cake every baked in Dublin, weighing 190 pounds, was made to celebrate the city's millennium in 1988. The cake, never eaten, was finally thrown out in 1991.

12. Dublin contains 46 rivers and streams including; Delvin, Hurley, Corduff, Finglas, and Shanganagh.

13. Nelson's Pillar was blown up in 1966 to mark the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising (http://alinefromlinda.blogspot.ca/2017/03/easter-rising-1916.html) . It now lies in a heap in the valley in County Wicklow.

14. Dublin contains five areas which end in the letter "O": Rialto, Marino, Portobello, Phibsboro, Pimlico.

15. The original name of Trinity College was Trinity College near Dublin. The city was a lot smaller when the college was founded.

Source: http://www.irelandrevealed.com/facts-and-interesting-stuff-about-dublin/45-facts-of-so-you-think-you-know-dublin/

Sunday, 12 March 2017

Drisheen, Crubeens & Periwinkles

Here are some typical Irish dishes:

1. Drisheen: a type of pudding made from cow's, sheep's or pig's blood.

2. Periwinkles: sea snails boiled in salt water.

3. Coddles: layers of pork sausages or bacon usually thinly sliced; somewhat fatty back bacon with sliced potatoes and onions.

4. Colcannon: Mashed potatoes with kale or cabbage.

5. Barmbrack: a leavened bread with sultanas and raisins.

6. Boxty: finely grated raw potato and mashed potato mixed with flour, baking soda, buttermilk and occasionally egg, then cooked like a pancake on a griddle

7. Champ: mashed potatoes and chopped scallions with butter and milk.

8. Crubeens: boiled pig's feet.

9. Farl: a triangular quick bread.

10. Pastie: a round, battered pie of minced pork, onion, pototo and seasoning.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Irish_dishes

1. Drisheen: a type of pudding made from cow's, sheep's or pig's blood.

2. Periwinkles: sea snails boiled in salt water.

3. Coddles: layers of pork sausages or bacon usually thinly sliced; somewhat fatty back bacon with sliced potatoes and onions.

4. Colcannon: Mashed potatoes with kale or cabbage.

5. Barmbrack: a leavened bread with sultanas and raisins.

6. Boxty: finely grated raw potato and mashed potato mixed with flour, baking soda, buttermilk and occasionally egg, then cooked like a pancake on a griddle

7. Champ: mashed potatoes and chopped scallions with butter and milk.

8. Crubeens: boiled pig's feet.

9. Farl: a triangular quick bread.

10. Pastie: a round, battered pie of minced pork, onion, pototo and seasoning.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Irish_dishes

Labels:

barmbrack,

boxty,

champ,

colcannon,

crubeens,

drisheen,

farl,

Irish cuisine,

pastie,

periwinkles,

pig's feet

Saturday, 11 March 2017

Are There Really No Snakes in Ireland?

Legend has it that St. Patrick drove the snakes out of Ireland in the 5th Century. While it is true that Ireland has no snakes it is for geographical, not human, reasons. When the snake evolved about 100 million years ago, during the late Cretaceous period, Ireland was completed submerged under water. During the Cenozoic Era, about 65 million years ago, the world started to dry out and vast grasslands dominated the Northern Hemisphere.

Predecessors to the cobras and pythons first appeared 50 million years ago while modern day cobras and pythons appeared 25 million years ago. Today, snakes are found everywhere but Ireland, New Zealand, Greenland, Iceland and Antarctica. Serpents haven't figured out how to migrate across the ocean to a new home. While land bridges formed over past millennia, snakes would have frozen during the Ice Age.

How did the myth of St. Patrick and the snakes evolve? In Christian cultures, snakes have always symbolized paganism starting with the serpent that tempted Eve in the Garden of Eden. Therefore, St. Patrick, who helped convert many pagans to Christianity in Ireland, would be a likely candidate to banish the snakes.

Source: http://www.rte.ie/tv/scope/SCOPE4_show03_snakes.html

Friday, 10 March 2017

Ireland's Topography

Kilkenny Harbour forms a natural barrier between Galway and Mayo courtesy https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geography_of_Ireland.

1. Ireland, which occupies 84,4009 square miles, is about half the size of Arkansas.

2. It's greatest length, between Toor Head, County Antrim and Mizen Head, County Cork, spans 302 miles.

3. It's greatest breadth, from Dundrum Head, County Down to Annagh Head, County Mayo, spans 104 miles.

4. Its highest cliffs are found on the northern coast at Achill Island, County Mayo, an area which suffered an earthquake in 2012.

5. The longest river, Shannon, flows 204 miles before pouring into the Atlantic Ocean at Limerick.

6. The island's coastline runs 1907 miles.

7. The largest lake, Lough Neagh, measures 153 square miles and supplies Ireland with 40% of its water.

8. Ireland consists of four provinces broken up into 32 counties, six of which are part of Northern Ireland.

9. The mountains are composed of granite, sandstone, limestone, karst and basalt.

10. Ireland has 4,633 square miles of bogland consisting of blanket bogs and raised bogs.

Thursday, 9 March 2017

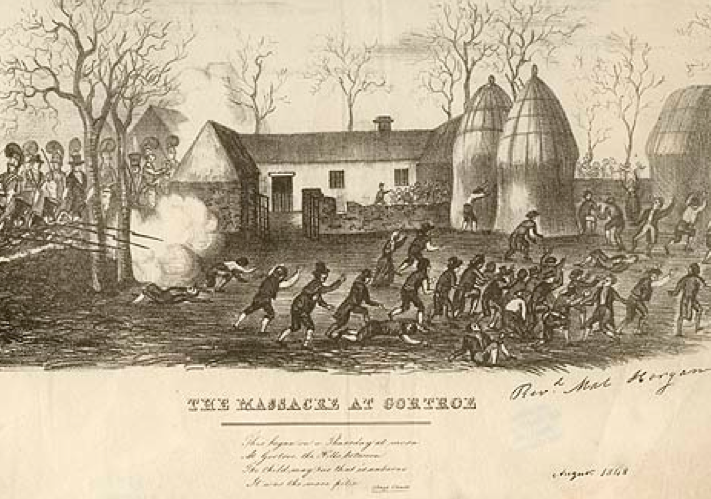

The Tithe War

"In something of a dress rehearsal for the Land War of the 1880's, the Tithe War began in Kilkenny, Wexford and Tipperary with public meetings of men carrying hurley sticks which could be represented as sporting occasions." (Myles Dungan)

Tithes were levies paid by Irish farmers, not landlords, to the Church of Ireland, the established church. These tithes helped keep the clergy in relative comfort. The farmers, in the meantime were bled dry, leading to great unrest in 1830's Ireland. The Catholics bitterly resented these tithes. While the rent they paid gave them a roof over their heads, they received nothing in return for the tithes.

"In something of a dress rehearsal for the Land War of the 1880's, the Tithe War began in Kilkenny, Wexford and Tipperary with public meetings of men carrying hurley sticks which could be represented as sporting occasions." Soon, Irish farmers were refusing to pay the tithes as a form of protest.

On June 18, 1831, a tragedy occurred in Newtonbarry, Wexford where an Anglican rector had seized the cattle of farmers who refused to pay the tithe. As the cattle were being auctioned, some of them got loose. In trying to retrieve their cattle, the farmers were fired upon by Protest militia. When the gunpowder cleared, eighteen farmers were dead.

The following December, vengeance was in the hearts of the Kilkenny farmers who attacked a force of constables armed with summonses for those who had refused to pay their tithes. The vigilante group tried to get the process server, Edmund Butler to eat the summonses, but he refused. Armed with rocks and pitchforks, they attacked the constables, killing thirteen of them, including Butler.

Finally, in 1838, the Irish court ruled that the farmers would no longer pay the much hated tithes, but rather the landlords would. However, it was a bittersweet victory: the landlords passed the payments on to the farmers in the form of higher rents.

Source: https://mylesdungan.com/2013/06/14/on-this-day-18-june-1831-the-newtownbarry-massacre-the-tithe-war/

https://mylesdungan.com/2013/06/14/on-this-day-18-june-1831-the-newtownbarry-massacre-the-tithe-war/

Wednesday, 8 March 2017

Easter Rising 1916

"I die that the Irish nation might live!" (Sean McDermott)

It made the front page of the New York Times eight days in a row. It divided an island. Sixteen of its leaders were executed, all of which have railway stations named after them.(http://www.thejournal.ie/irish-rail-1916-2-2744978-Apr2016/)

The Easter Rising began on East Monday, 1916. It was planned by the Irish Republican Military Council. Contrary to what the name implies, the Council's members were not all politicians or military men. Thomas McDonough and Joseph Plunkett were poets. Plunkett married his fiancee only eight hours before his execution. Patrick Pearse was a writer and a schoolteacher. James Connolly, a republic leader, was not even born in Ireland but in the United States. Connolly was so injured that he was carried on a stretcher to his execution. Eamon de Valera, a fellow American was a prominent politician and statesman in Ireland. Thomas Clarke, an Irish revolutionary who started the Brooklyn Gaelic Society, was English born. Sean McDermott, who editted the IRB newspaper Irish Freedom, wrote in 1916: "I die that the Irish nation might live!"

When the Rising began when the Irish Republicans took over significant buildings in Dublin, amid little resistance. When the fighting began in earnest, the Irish Republican troops outnumbered the British ones 1000 to 400. Within a week, that all changed; the British boasted 19000 troops to the Irish Republican's 1600. While fighting occurred in various parts of Ireland, the IRB were most successful in Dublin where they established headquarters at the post office. The deadliest battle took place at Mount Street Bridge in Dublin. The entire Easter Rising lasted only six days.

Rather than seeing the IRB leaders as heroes, they were initially considered traitors by many Irish citizens. Irish civilians incurred 154 deaths and 2000 injuries during the revolt. However, once the execution of the uprising's instigators began, the national mood changed. Songs were sung to honour the Rising's leaders, funds were collected to aid their families and Irish Republican flags appeared. While 3000 were arrested after the revolt, they were granted amnesty by the British government in 1917.

Tuesday, 7 March 2017

Titanic by Numbers

The White Star Line wanted a luxury liner to compete with the Cunard Line's Lusitania and Mauretania. Not to be outdone, it built three ships: Olympia, Britannia and Titanic. Here are some facts about the most famous of three:

1. 26 months: the length of time it took the Belfast workers to build the Titanic

2. 228 feet: the height of the gantry built over the Titanic, the world's highest at the time

3. 14,000: the number of workers employed to build the Titanic at Harland & Wolff Shipyard in Belfast, Ireland

4. 246: the number of injuries during construction

5. 8: the number of deaths during construction

6. 15: the number of predicted deaths based on the ratio of 1 death for every 100,000 pounds spent

7. 200: the number of rivets completed by a four man crew each day

8. 20: the number of horses to pull the main anchor

9. 49: the average workweek for shipbuilder

10. 2: the number of pounds for weekly wage

11. 6: the number of days shipbuilders worked (they quit early on Saturday and had Sunday off for church)

12. $166,000,000: the price tag for Titanic in today's dollars (it's still cheaper than the price tage for the 1997 movie Titanic which cost $200,000)

13. 3,000,000: the number of rivets used to construct a metal & iron hull

14. 401: the yard number given to the Titanic when her keel was laid down

15. 3,000: the approximate number of men who built the Titanic (20% of the workforce)

1. 26 months: the length of time it took the Belfast workers to build the Titanic

2. 228 feet: the height of the gantry built over the Titanic, the world's highest at the time

3. 14,000: the number of workers employed to build the Titanic at Harland & Wolff Shipyard in Belfast, Ireland

4. 246: the number of injuries during construction

5. 8: the number of deaths during construction

6. 15: the number of predicted deaths based on the ratio of 1 death for every 100,000 pounds spent

7. 200: the number of rivets completed by a four man crew each day

8. 20: the number of horses to pull the main anchor

9. 49: the average workweek for shipbuilder

10. 2: the number of pounds for weekly wage

11. 6: the number of days shipbuilders worked (they quit early on Saturday and had Sunday off for church)

12. $166,000,000: the price tag for Titanic in today's dollars (it's still cheaper than the price tage for the 1997 movie Titanic which cost $200,000)

13. 3,000,000: the number of rivets used to construct a metal & iron hull

14. 401: the yard number given to the Titanic when her keel was laid down

15. 3,000: the approximate number of men who built the Titanic (20% of the workforce)

The Titanic under construction courtesy http://www.titanicfacts.net/building-the-titanic.html.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)