"This is what I do." (Lisa Allison)

As most of you know, seven years ago my sister Lisa suffered a ruptured brain aneurysm followed by a massive stroke at the tender age of 45. She now lives in a nursing home. Despite the odds, Lisa has proven the doctors wrong over and over again by regaining abilities they said she would never regain (see "Painting a Portrait of Stroke Recovery" (http://www.christiancourier.ca/images/uploads/past-issues/2015April13c.pdf - page 12). One of those abilities is painting. Before the stroke, Lisa was a graphic artist.

As most of you know, seven years ago my sister Lisa suffered a ruptured brain aneurysm followed by a massive stroke at the tender age of 45. She now lives in a nursing home. Despite the odds, Lisa has proven the doctors wrong over and over again by regaining abilities they said she would never regain (see "Painting a Portrait of Stroke Recovery" (http://www.christiancourier.ca/images/uploads/past-issues/2015April13c.pdf - page 12). One of those abilities is painting. Before the stroke, Lisa was a graphic artist.

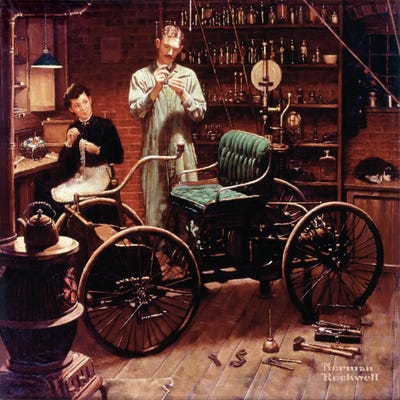

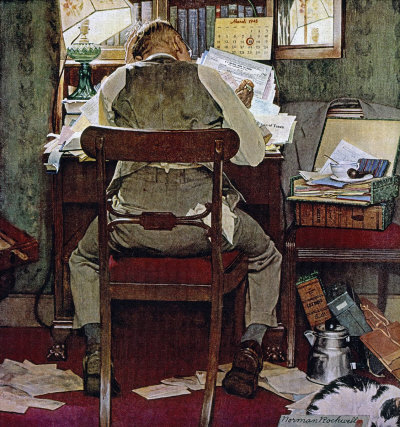

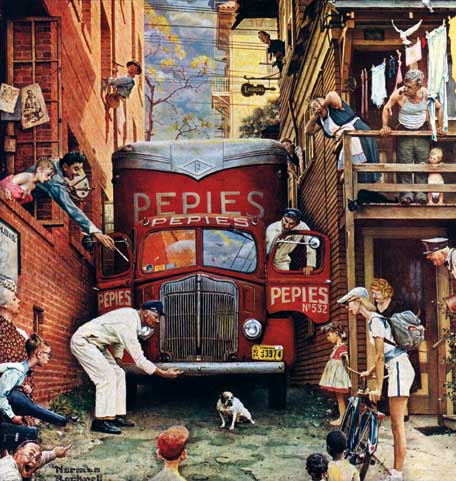

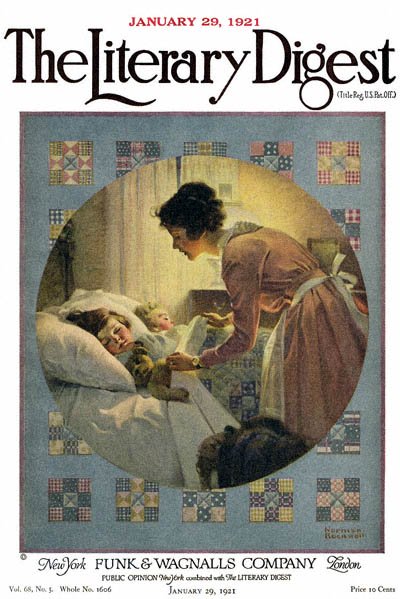

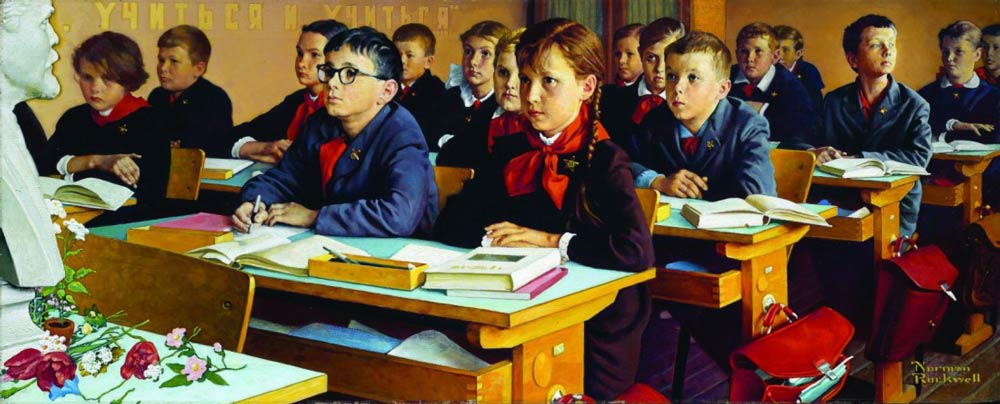

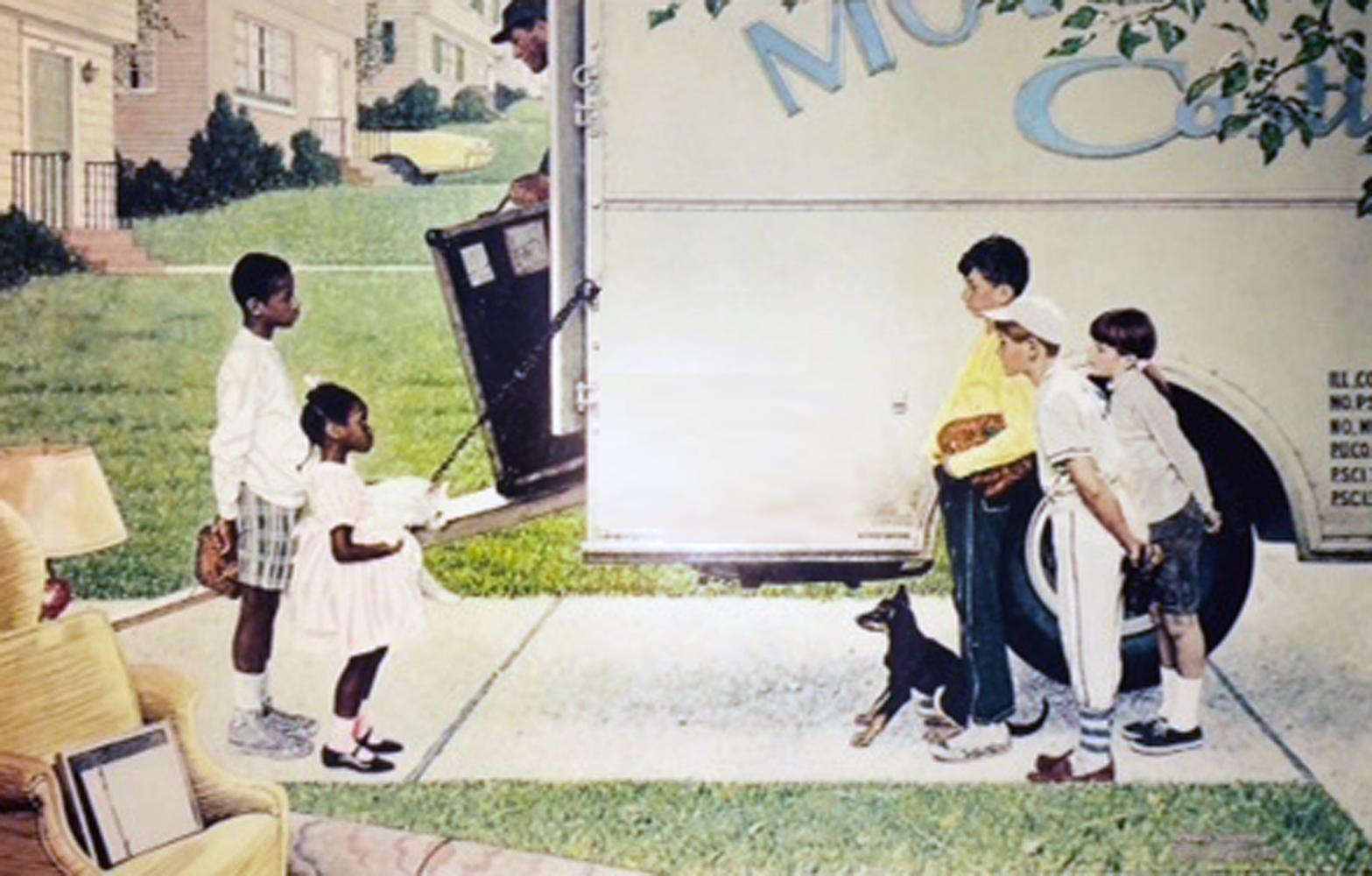

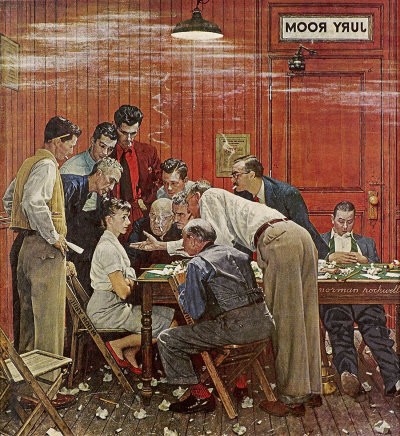

Lisa Allison's painting circa 2016 courtesy Laurie Candela.

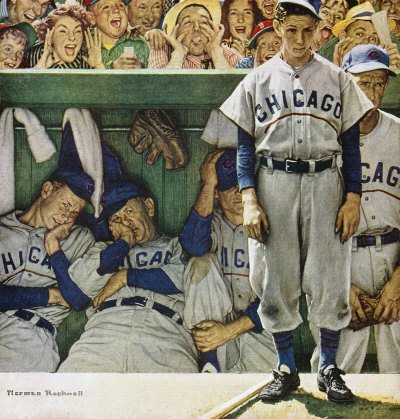

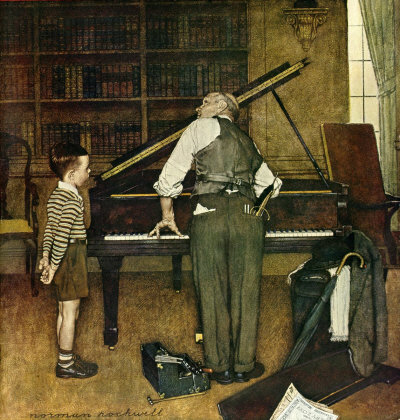

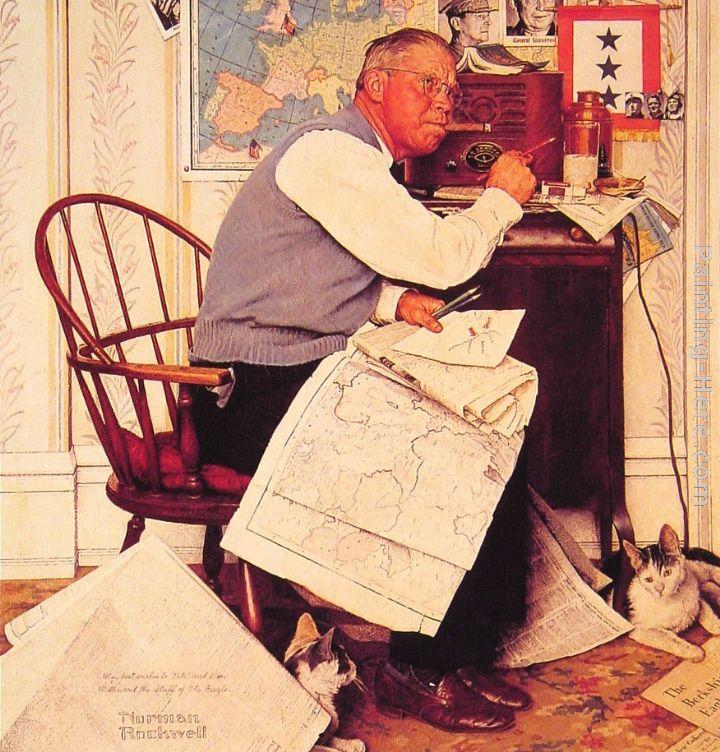

Lisa phoned me yesterday. It was a timely phone call. I mentioned that I have been blogging about the famous American artist Norman Rockwell. I knew she would be very familiar with the name, but other than that, I wasn't sure what she would remember about his work. One by one, I went over the paintings I had chosen. One by one, Lisa pointed out details that only an art connoisseur would know.

Lisa remembered the ever popular Saying Grace. She recalled Shuffleton's Barbershop. But when I came to Before the Shot, she started to warm up. "That's the one with the giant syringe," she explained. I mentioned Choir Boy Combing Hair at Easter and Lisa pointed out: "The boy's mouth was open as he looked at himself in the mirror." When I brought up Walking to Church, Lisa said: "Yes, they all have Bibles tucked under their arms." I was thoroughly impressed when she perked up at the mention of Marriage License, saying: "The bride has a bright yellow dress on." When I said the title Art Critic, Lisa said: "Yes, he's the one with the large palette of paints in his hand."

I started this month's blog topic with the post "It's All in the Details". The details Lisa remembered seven and a half years after the stroke are quite remarkable, considering they come from a woman who sat in a coma for six weeks. There was a time when the doctor would pound on her chest, just looking for any response like the flickering of an eyelid or the twitching of a toe. Now she has lengthy, stimulating conversations about art. When I pointed out my amazement, Lisa's response was simply: "This is what I do."

http://christianmotivations.weebly.com/christian-motivations-blog/category/max%20lucado/20

Lisa Allison's painting circa 2016 courtesy Laurie Candela.

Lisa Allison's painting circa 2016 courtesy Laurie Candela.

_10.jpg)