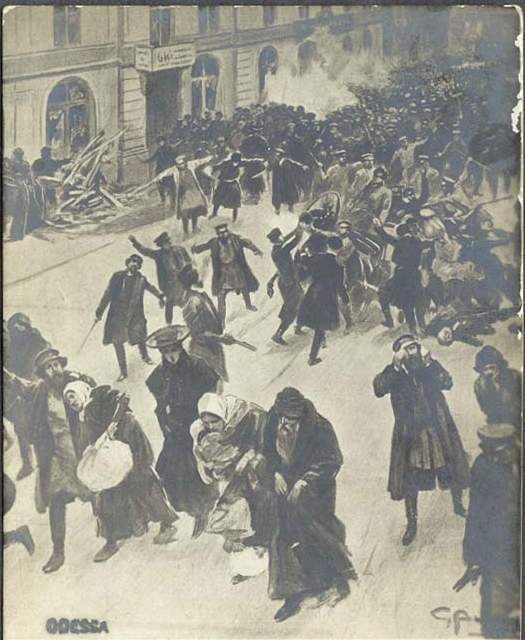

"If you hate, you lose yourself. There's nothing left in this world after hate. I can't hate. I have never been taught to hate. Even after pogroms, after all that happened in our town, my father tried to explain...I was ten years old. I asked the question: Why? There was no answer to it There still isn't." (Clara Rudder)

Clara Rudder grew up in a devout Jewish family in the Carpathia Mountains in Poland. Her father owned a store which sold pots and pans. Her mother raised her and her siblings along with a niece. The Rudders hailed from Spain where they had lived for four hundred years. The Polish king encouraged Jews to come to his country in order to build commerce.

On the Sabbath, someone came to the Rudder's house to warn them that their town was about to undergo a pogrom. Clara's father warned the congregation at their synagogue to escape, taking their silver menorahs with them. The Rudder's fled to a Gentile's house where he hid them in his barn. When they returned the following day, all the doors had been broken, all the windows shattered and sacs of flour, which were too heavy to carry, were doused with petrol.

The only structure left untouched was the Rudder's store, perhaps because Mr. Rudder was such an honest businessman, or perhaps simply because the invaders didn't need any pots and pans. Mrs. Rudder took the biggest pot they owned and made meals for the community. Little Clara said they did not sleep for four weeks.

Yet, when Clara returned to school, the children shouted at her: "Get out of here!" Vowing never to raise her own children in Poland, Clara planned that day to immigrate when she grew up. At 20, she suggested Palestine as a destination to her mom, to which she replied: "You're going to split rocks in Palestine. I did not bring up a child of mine to go and split rocks."

Clara's brother and sister moved to Antwerp, Belgium and she suggested that she immigrate there. She encouraged her parents to join her, but they felt like having been born and raised in rural Poland, that's where they should stay. Clara dated a young Jewish man who studied in Prague, Czechoslovakia. Only three percent of Jewish Poles were accepted at university, forcing the remainder to study elsewhere. After Clara and her boyfriend got engaged, she invited him to join her in Belgium and he agreed to continued his studies there. However, her fiance, rejected at the Brussels university chose to return to Poland rather than immigrate. Clara returned the ring to him.

After moving to Belgium, Clara met a diamond dealer named Paul. They married and had a son. In the meantime, Hitler's panzers started rolling over Europe, forcing the couple to move to France. When the Nazis reached France, the couple was driven back to Belgium. Clara was more determined than every to get out of Nazi occupied Europe.

In 1940, a Paraguay attache offered to drive the couple across France to Spain and then Portugal. Clara's sister, who had taken the trip first, wrote her a letter: 'Everything is fine, we are across the border. Take two valises and come..." Closing up their apartment, the couple took some diamonds and $12,000 in cash for the journey. Stopping in Perpignan, France to secure visas, the Paraguay attache explained that he could not take them any further as his car had broken down. The couple, planning to continue their journey by train, realized they had only $1,000 left in their possession. Their driver had absconded with the bulk of their savings.

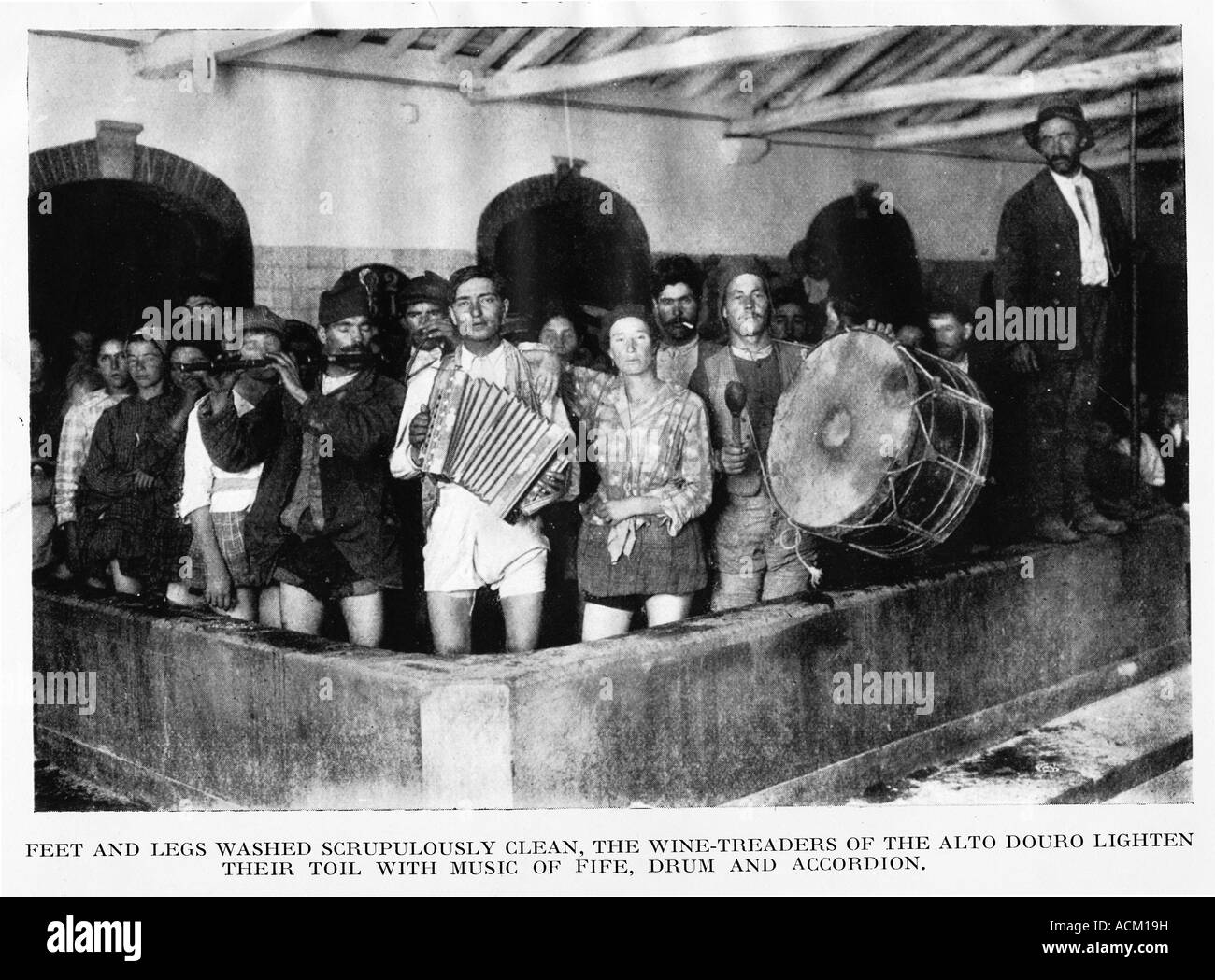

Reaching Lisbon, Clara and her family booked passage to America on a Greek ship. However, Germany invaded Greece in the meantime and the ship never sailed. It took three months for her to find another boat, this time a cattle boat. On the twelve day voyage Clara, nervous about the mine infested waters, barely ate.

When the boat finally reached Ellis Island, Clara was asked what she wanted. "I want a good glass of milk...The milk tasted like cream. It was delicious." However, Clara was disappointed with Ellis Island. She said that the authorities would not let them off the island. She felt like she was in jail. What made matters worse, was that Clara could not speak English. The big room where the immigrates were processed was filled with 300 to 400 people. "I couldn't breathe," explained Clara.

After seven weeks at Ellis Island, the mystery as to why Clara and her family wasn't released was cleared up. Clara's brother in law, had given the money for their trans-Atlantic passage to a lawyer. The lawyer had taken the money and then wrote the ship company a cheque which had bounced. The family was being detained for the passage money.

After the Second World War, Clara discovered that her parents, her cousins, the entire town had been murdered, gassed in the ovens at Auschwitz.

Inmates forced to carry rocks at Mauthausen Concentration Camp in Austria courtesy https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extermination_through_labour.

_the_Building_of_Ziraat_Bankas%C4%B1_(Agricultural_Bank),_1930s_(16851406391).jpg)